In general as a coach, I choose to avoid using punishment as a motivator. The method reeks of domination, intimidation, and fear, all of which poison the waters of learning. While punishment may sometimes ‘succeed’ in the short term—it also breeds resentment and disenchantment. Even then, as my friend and colleague Luca Canever points out, it only works as long as the learner keeps the potential consequence in mind. In other words, as long as she occupies mental bandwidth that would be better applied to whatever task lies at hand. Especially if delivered with anger or malice, punishment remains both cruel and crude. When given the option to bare such teeth, I continue to say “No, thanks.”

My evolving clarity on that preference has me looking ever more closely at the structure of my practices and even of the drills I use when coaching. What about the benefit of using ‘punishment’ as a conceit, a constructed game playfully agreed upon by those involved? Or one, at least, ‘imposed’ playfully by the coach or teacher?

Take, for example, Queen of the Hill, one of my favorite drills to use with the Northfield Mount Hermon softball team. I want my players focused on the precision of their technique during throwing warm-ups. Almost every athlete can improve her form and that, in turn, will increase her power, reinforce her accuracy, and help her prevent injury. Grip on the ball. Height of the elbow. Strong point to the target. Proper footwork. Solid follow-through. We have plenty that demands our attention.

A skillful throw is a beautiful thing.

—–

Photo courtesy of Risley Sports Photography, 2012

www.jtrsports.net

Of course, warm-ups also serve as the most social part of practice. Transitioning from their school day, the girls want to gossip, to catch up on news, to laugh and rib each other. I recognize—and even appreciate—the value of such interaction. Unfortunately, there’s almost always a strong inverse correlation between the volume and frequency of such chatter and the focus on and effectiveness of the throwing technique. The more they talk, the more they go through the motions. The more they ingrain improper muscle memory.

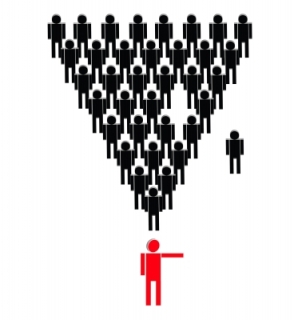

So we use Queen of the Hill. Throwing pairs line up with one partner on the left field foul line and the other in foul territory. Each pair leaves eight feet or so of space between themselves and the next pair so the group as a whole extends down the foul line. The two closest to home plate qualify as “Queens of the Hill,” and the others aspire to move up into that spot. Girls maintain their relative position by completing a clean throw and catch. If a pair overthrows a target or flubs a catch, that pair cedes their spot in the ‘hierarchy’ and sprints to the bottom spot along the foul line.[1] If they forget (or choose not) to actually sprint, the whole team stops, drops their gloves, and comes to the foul line for a single wind sprint out past centerfield and back. Then they all resume their places in the chain and continue.

Full-speed hustle forces errors from the other squad.

—–

Photo courtesy of Risley Sports Photography, 2012.

www.jtrsports.net

For sure, the drill sharpens focus, improves hustle, helps with throwing form, and increases accuracy—at minimum for the duration of the drill, but going forward as well. Energetically, I don’t sense the drill building fear or resentment. Usually, it seems to stoke the girls’ competitive fire and playful spirit. Again, their focus and form both improve dramatically. Other coaches have had success with similar set-ups.

All that said, the drill also employs a form of punishment. I may not yell or scream, but I am looking to decrease unwanted behavior (distracted chattering and lollygagging between spots on the field) by adding in an aversive, something ‘unpleasant’ like losing a place in line or having to sprint, either as a pair or as a team. I could frame it for myself that I’m promoting and rewarding the desired behavior—stay focused and successful and you keep moving up—but such a frame seems a bit dishonest, or at least a cop-out. The underlying structure remains punishment. It may be mild, but it’s still punishment. And that sits uneasy within me, at best.

I don’t yet have a complete answer for myself. I know that my attitude as a coach greatly affects the tone of the experience. If I’m angry or disappointed—or even appear that way, sharpening my voice or rolling my eyes—I communicate an emotional or relational failure on their part, as if they’ve injured our personal connection. That’s not a healthy dynamic and it doesn’t help learning. If I can stay neutral and even playful in tone, then I’m holding them accountable while also recognizing we’re playing a game. That I usually participate in the drill myself lessens the ‘punishment’ aspect even further. If I drop a ball or overthrow a target while warming up, my partner and I have to sprint as well. If we or someone else lags in our sprinting, I’m on the foul with everyone else, racing to centerfield and back.

Moreover, the cost of failure in this case remains relatively light—an intense, but short sprint—and actually serves as another improvement to one’s game. When you make a mistake during the live action of a game, going full-tilt to recover might preserve a run—and a win. Hustling matters. The so-called aversive delivers a hidden benefit. Along the same lines, the drill delivers other valuable messages. When you as an individual mess up during a game, it does, in fact, affect the whole team. There is a consequence. And, the whole team can have your back. If teammates run to the foul line for our corrective sprint with enthusiasm, knowing that you didn’t intend to mess up, we communicate togetherness. We build resilience.

Knowing a team and its individual players well also makes a difference in how such a drill gets received. Most likely, it will work better on some days than on others. The moment can alter the mindset. It also seems reasonable that the joy in such a drill can evolve over time. Maybe we don’t like the ‘punishment’ at first, but we can fake it until we do. Extend the arms while running your sprint. Find a chant to change brain chemistry. Smile—or imagine taking a bow—to flush out the failure and regenerate optimal attention.[2] In that way, the ‘punishment’ becomes an opportunity to develop other skills and recoveries we actually need during the heat of competition. The benefits abound.

Good teamwork leads to jubilation.

—–

Photo courtesy of Risley Sports Photography, 2010

www.jtrsports.net

My questions still hold, however. I wonder about the rules for moving up, for example. Players may achieve perfection in the quality of their own work, but never reach the queen’s ‘throne’ without others making mistakes. On one level, the game teaches the girls to celebrate their teammates’ failures. Occasionally, I’ll see girls pull back on the intensity of their warm-ups, thinking that if they don’t throw hard that they’re less likely to make a mistake. I can usually get them to shift back just by pointing their adjustment out, but the ‘punishment’ of the drill may work at odds with my desire for fearlessness. More subtly, I wonder if using such a game undermines the positive reinforcement spirit I’m trying to instill during the rest of our practice. Maybe I’m chipping away at trust that I could well use for detailed instruction later. And this all may happen below the surface of awareness. “It’s all good,” the girls might say. But is it really?

I’ll admit that part of me likes never knowing for sure. The uncertainty helps me preserve greater alertness and curiosity. I pay attention to how my words and posture affect the girls’ demeanor. I listen for the enthusiasm—or lack of it—in their vocal tone and body language. I stay open to making adjustments on the fly. Given the larger goals I carry for the team, however—to help each player improve her skills, to build a resilient and supportive unit, to play our best and win ballgames—I can see that greater certainty could help. Positive reinforcement remains a subtle and challenging art. I know I’m just a beginner.

Good point. This post reminds me Rozales Ruiz’ lecture at Clicker expo 2012. His ideas was that we’re not “just reinforcing” or “just punishing” a behavior. If I lure my dog to sit with a treat, I’m reinforcing the sit (the behavior wil appear more often) but at same time I’m punishing everything else (the behaviors will appear less often) When your girls have to sprint are you punishing the lack of focus or negatively reinforcing the focused behaviors you want? The answer is hidden, as always, in the consequences: which behaviors the drills have increase?