Shortly after the previous post, The Wisdom of Mistakes, appeared in the Northfield Mount Hermon School alumni magazine, a trio of students in the Video as Visual Art class asked if they could interview me for further reflections. I gladly obliged and felt even more thankful after hearing the sophistication of their questions—them boys made me think. Of course, they’re living and learning in the pressure-cooker world of a private prep school, but I think their queries will resonate with others in many settings. Here’s a refined version of the conversation we had.

No buffer means even small stresses can put us over the edge.

* * *

Photo courtesy of freedigitalphotos.net

How do you feel pressure contributes to negative feelings of failure?

We have to ask what kind of pressure we’re talking about. Certain kinds become particularly poisonous to learning because they amplify negative feelings. In part, that can happen when we jam our schedules too tight. We pack in more and more demands—you guys know this well—and miss out on the open time and space needed for integration and consolidation. In the process, these ongoing high-adrenaline demands blow our buffers out. Then, when challenge comes, we lack any cushion. It’s like metal scraping metal or bone pushing into bone. In that mode, even a small failure can prove exceedingly painful, making it hard to learn from mistakes.

It can also get tough when pressure gets linked to judgment of the person involved—if you don’t reach this level, you’re a nobody. That’s especially deadly. You may not hear such threats exactly, but the same message can be coded into other language, both verbal and non-verbal. A roll of the eyes or a shrug of the shoulders that expresses disapproval: those, too, can cut deep and interrupt the learning flow.

This is where mindset matters so much. If you and your teachers have a fixed mindset—thinking that your abilities and talents are given at birth—then you spend your days trying to prove yourself. If you’ve got a growth mindset, you know your abilities continue to develop through your dedication and hard work. In that mode, the pressure—as long as it leaves that time and space for integration—becomes a force for advancement.

Note that community makes a big difference too. If you’re trying to learn in a growth mindset but everyone around you lives and breathes in a fixed mindset haze, you’re going to have a hard time bucking that current. In contrast, the tide of a growth mindset lifts all boats.[1]

In the learning or advancing process, do you think we should relieve the pressure we put on young people? Or do you think pressure pushes people to succeed?

As we just mentioned, mindset matters. Young people with a fixed mindset might fold under minimal pressure. Those with a growth mindset might thrive under great stress.

Even without that model, though, we can acknowledge that pressure does push some people to change. One of my close friends became an outstanding athlete and winning coach because he so hates to lose. Any mistakes he make drive him to improve. And I know he’s not alone. We all depend on some stress in order to grow. The pearl needs the sand in the oyster. The sword needs the heat of a forge. At the same time, as we’ve also mentioned, too much pressure can collapse the house of cards. The trick is finding the right balance.

Your question reminds me of a story about the Buddha. He grows up in the lap of luxury, his lordly father sheltering him from any troubles. Ornate palaces, delicious foods, gorgeous attendants, and able-bodied friends: Siddhartha seemingly has it all. Later, after he escapes the palace confines and catches a glimpse of suffering, he retreats to a life of asceticism for seven years, surviving without pleasure or sustenance.

It’s only after having lived both those extremes that he overhears a passing musician on a boat instructing a student: If the string is too tight, it will snap. If it is too loose, it will not play. In that moment, Siddhartha realizes he’s been searching in the wrong places and commits to finding a Middle Way. He builds his body back to full strength and goes to sit under the Bodhi tree until he eventually reaches enlightenment. Too little pressure leaves us slack. Too much makes us snap.

Of course, the ideal tension is different for each learner and that’s what makes effective instruction so difficult. As a teacher, you have to pay super close attention to how your students respond—and to your own preferences and predilections as well. As a learner, you sometimes have to tune out or translate your teacher’s voice so you can honor what works best for you.

Personally, I still lean towards the premise of positive reinforcement. That model suggests that, yes, you can get short term behavioral adjustment through force or jacked-up pressure but that change motivated by the learner’s own curiosity ultimately becomes deeper, more joyful, and longer-lasting. When criticized, I might work hard to prove you wrong or earn your praise. I might well learn, but I’m also consuming valuable time and energy on an emotional component that muddies the lesson. If I can focus all my faculties—emotional and intellectual—on the task at hand, that’s a better platform for learning.

Is there a point where failure is no longer effective as a learning tool and one should accept a challenge as impossible?

Absolutely, there are times where it’s best to just move on. That might be in the big picture, as in, yep, this just ain’t gonna work out. (I’m remembering one crush, in particular, where I realized that absolutely nothing I did was ever going to gain her favor.) Or it might be in a given moment, where our frustration levels have peaked and we’re simply not capable of making progress. So we step aside, let the annoyance subside, and then come back at a later date. High level animal trainers know this well: back off, ask for a few well-developed behaviors you know will generate success, and wait for the next training session.

No information’s getting through once the defenses get kicked up.

* * *

Photo courtesy of freedigitalphotos.net

Again, this is where the judgment of too much stress comes in. If I feel pressure as attack, I’m likely to get reactive and defensive. My amygdala—the part of the brain that signals fight, flight, freeze or faint—fires up and hijacks any higher-level learning. A simple “No!” can trigger that kind of reaction, whether it’s an outside voice or our own self-judgment. Too many “failures” in a row can lead to the same outcome. In that brain space, you can forget about abstract reasoning, skill development, or high-level synthesis. Information will not pass through and settle in. The soil’s simply not receptive to the seed.

When we can move out of reaction mode into a more fluid and flexible response mode, then we can begin to learn again. Then the pathways reopen. Again, teachers and students need to monitor that line for themselves. When do I get reactive? What triggers me into that space? How do I bring myself back out of that defensiveness? Not surprisingly, developing the skills of mindfulness can prove incredibly helpful here. You can learn to catch the reaction just as it’s happening and pause with a moment of awareness. What other options are available to me?

Can you talk about the distinction between accepting failure as a step on the road to success and being constructively motivated to erase that failure?

The more I’ve been learning about failure, the more I think we have to grow in our relationship to it. Most of us are conditioned—or have conditioned ourselves—into what my friend Matt Smith calls the “cringe mode” in response to failure. We tense up, close off, and launch into a litany of self-judgments. We think that reaction protects us from further injury: if I communicate that I’m upset with my mistake, maybe you’ll back off from piling on. But it also shuts us down.

So maybe the first phase is to learn to take failure as motivation. My friend who’s the athlete and coach would applaud this step. Feel the frustration of that moment and use it as fuel. Work hard to make sure the mistake doesn’t happen again.

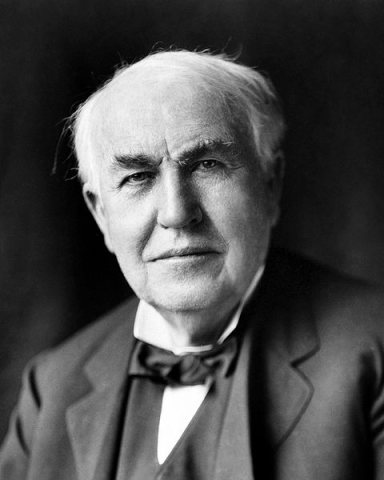

A second phase would be to view the error as one step on the road to success. It’s not just a foil, it’s a source of information. This echoes the growth mindset model, gathering more and more information from each iteration. Like Thomas Edison going through trial and error on his way to breakthrough innovation, we test our prototype behaviors, knowing we’ll fail along the way. Heck, we need to fail along the way. That’s how we learn.

A third phase makes even more space, admitting that we might be labeling our “failures” too soon. Maybe the mistake opens a door or leads to a path that had previously remained invisible. My grandmother used to say “Everything happens for a reason.” I don’t know if I believe that, but I do know that I can choose to use whatever happens, good or bad, for my betterment. In retrospect, it will look like that failure happened for a reason—and we won’t be able to imagine our lives without that so-called mistake.

Good improvisors live in a fourth phase that I find the most compelling, embracing failures as gifts. Audiences love to watch improv actors walk the crazy edge of failure—who knows where this scene is headed? The most delightful moments come not when a scene unfolds in perfect fashion, as if rehearsed, but rather when someone stumbles and then recovers with artful joy. Usually, that happens with the help of stagemates as well. The merry band justifies the failure, using it as exactly what needed to happen. The skillful response turns the mistake into a jewel. Admittedly, that’s a rarefied place to get to, truly welcoming failure for the gift it represents. It’s a radical level of self- (and other-) acceptance that may seem impossible. But there’s no reason we can’t aim for it.

[1]This is one of the great benefits of The Failure Bow. In that theater exercise, we step to the front of a stage, admit a mistake out loud and proudly declare I took a risk! I failed! I’m still here! WOO HOO! Rather than flinch, the “audience”—our team—roars in approval. In that moment, the improvisor gets to experience viscerally a more healing approach to failure. Yes, the community says. We saw the misstep. AND, we celebrate your effort, your transparency, and the courage it takes to get back on your horse for the risk of another creative response. How would hearing that kind of response to failure open up new channels of innovation and learning?