The previous post discussed the history and varied application of The Failure Bow, a well-loved improvisational theater technique for returning to the present moment after a seeming mistake. This post, Part 2, explains recent body chemical research that shows how and why the Bow works—and argues for its wider application for creating and spreading confidence, authenticity, and joy.

We know that the Failure Bow helps improvisors recover from goofs and flubs so they can stay present in the streaming chaos of an unfolding scene. Can similar physical stances significantly shift how your life unfolds? Amy Cuddy, social psychologist and associate professor at Harvard Business School, puts forward mind-blowing evidence to argue convincingly that, yes, they can.

In a TEDGlobal 2012 talk given this past June in Edinburgh, Scotland, Cuddy outlined her research, offering a “free, low-tech life hack that takes two minutes” as part of “Your Body Language Shapes Who You Are.” Almost everyone will acknowledge the importance of non-verbal, interactive communication. We make big decisions based on such information, and often do so in a heartbeat: whom we hire, whom we go out with, whom we vote for, and the like. We take it as a given that others’ stances, gestures, and non-verbals matter to our experience—and that ours matters to others.

Usain Bolt takes the proud stance of a champion. Image courtesy of Stephanie Kempinaire. (http://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/puma-nordic/images/puma-aw14_ff_bolt-325510)

Cuddy and her colleagues started their investigations by honing in on the dynamics of dominance and power at play in non-verbal expression. Those with positional power (CEO’s, rulers, champions, and the like) open themselves up, making themselves big and taking up space. We do this both when we have power and when we feel powerful. Even athletes blind from birth will adopt a similar stance after claiming a victory, even though they’ve never seen anyone else do the same: chest open, chin up, arms wide and high.[1]

Those without power—or who feel powerless—do the opposite, closing in on themselves to lessen the space they occupy. Perhaps a leg crosses over the other, an arm swings in front of the chest, or a hand reaches up to the face. Almost every human interaction involves some negotiation between levels of power. We meet, greet, and relate in complementary dances, acceding or asserting control to establish hierarchies and preserve peace.

Though Cuddy makes no mention of the link, experienced improvisors will surely recognize the similarity between her description of power positions and those we use to play high- and low-status characters on stage. Improvisors have other methods to suggest status as well, including speech patterns (slow, authoritative, complete sentences for high status; fast, hesitant and interrupted sentence fragments for low status), types of movements (slow and smooth for high status, fast and herky-jerky for low status), eye contact (steady and direct for high; fleeting and sideways for low), and verbal communication (evaluation and certainty usually raise the speaker’s status; deferral and uncertainty lower it). Here, too, the non-verbals communicate clearly. An audience can see relative power between characters from the back of the theater because it’s reflected in the actors’ bodies. The changing status dynamics mark shifts in relationship and reflect the arc of storylines or side dramas.

Having come to understand how power positions affect relationships between people, Cuddy and her colleagues wanted to point their evaluative lens in a different direction, wondering how our own body language affects how we feel. We smile when we’re happy, for example, but it also goes the other way. Faking a smile, like when we hold a pencil between our teeth, consistently and measurably elevates our moods. Would the same dynamic hold with non-verbal demonstrations of dominance? Could we make ourselves stronger leaders by taking the stances strong leaders take?

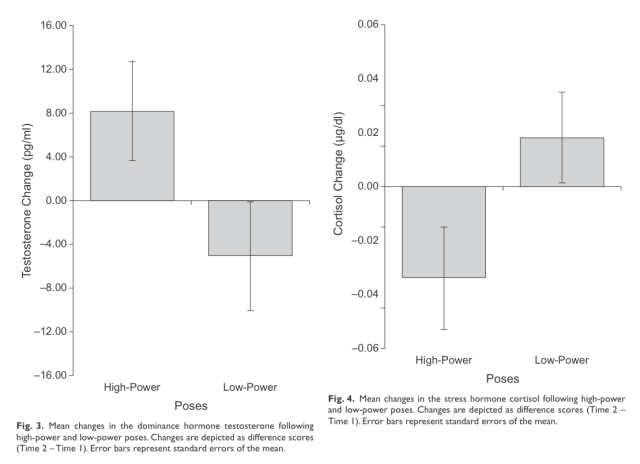

Cuddy began developing a test to find out. She knew that folks in positions of power (and those whose ‘natural’ tendency is to put their bodies in positions of power) tend to demonstrate more assertiveness, optimism, confidence, a greater ability to think abstractly, and an increased willingness to take on risk. The most respected forms of power don’t come through hair-trigger displays of temper but instead through calm direction in times of crisis. In hormonal terms, Cuddy found that those with more power tend to have higher levels of testosterone—the dominance hormone—and lower levels of cortisol—the stress hormone. These were the numbers to look for.[2]

The two high-power poses Cuddy and her colleagues used in the study. Notice the space-taking positions and open limbs.

For their experiment, Cuddy and her colleagues brought in test subjects and gathered saliva samples to measure baseline testosterone and cortisol levels. They than had subjects take either high-powered or low-powered poses—for just two minutes.

After that, subjects were asked how powerful they felt and were given the opportunity to gamble, a measure of risk-tolerance. Lastly, the experimenters took a second sample of saliva to test hormones after the fact.

The data demonstrated jaw-dropping results. To start, 86% of those who had put themselves into power positions showed a willingness to gamble versus just 60% of those who had adopted the low-power stances. Even more astounding, though, were the hormone numbers. Those who had assumed the high-power postures showed a 20% lift in testosterone and a 25% drop in cortisol levels. Those in low-power poses saw the reverse: testosterone levels decreased by 10% and cortisol levels increased by 15%. Again, these changes emerged after just two minutes of taking these poses! Cuddy and her colleagues were understandably gob-smacked by what they’d found, but wanted to make sure the changes they were seeing qualified as meaningful. Perhaps the shift would only last a short while and thus would not support greater impact.

To test the results further, Cuddy came up with a second experiment. Again, she and her associates had subjects do the two-minute power drill—some going high, some going low—and then enter a room for a job interview. Cuddy ramped up the stress of the meeting by hiring an interviewer trained to stay neutral in terms of body language, someone who would create an unnerving lack of social signals for the interviewees to monitor and gauge. Outside viewers then watched videotapes of the interviews without knowing who had been assigned to which group and without any sound—so they had no access to the content being exchanged. When the viewers were asked which candidates they would hire, they almost inevitably selected those who had taken on the high-power poses before the interview. Those candidates had come across as more assertive, more confident, more comfortable, more captivating, and more seemingly authentic. As Cuddy summarizes in the TED talk, those chosen had proven able to “bring their true selves with no residue (of shame).” In short, as she concludes, “Our bodies change our minds. Our minds change our behavior. Our behavior changes our outcomes….Tiny tweaks lead to big changes.” I’ll say.

While the numbers demonstrated do blow my mind, I’m not completely surprised by the thrust of the results. Improvisors know that taking on physical positions affects how well we perform. Part of what makes playing low status so fascinating is that it can actually put us in that mood. Simply shifting eye contact or adopting a closed stance makes it more difficult to speak in complete sentences. Keeping the head steady and moving slowly eases the task. As discussed in the previous post, the Failure Bow takes advantage of that dynamic in the opposite direction. If we react to missteps with an open-armed confidence, we change how we feel about having made the mistake. Rather than closing in to communicate to ourselves that we’re worthy of shame, we reprogram a different interpretation, showing our brains and hearts that we welcome the opportunity to learn and grow. Just thinking about the posture can reap some of the rewards—like it did for Patricia Ryan Madson in the story from my last post—but doing it physically creates an even stronger response in the brain. Low status or high status, we feel the stance we take. It has an effect.[3]

Cuddy’s research might lead one to think we should always choose high-powered positions—and I’ll say more about that in a minute—but in improv, we know that high-status characters are not any better than lower-status characters. A good story needs status relationships and changes to truly captivate an audience. If everyone on stage only played high status, the scene would look completely unnatural—and it would bore viewers to tears. (The same would be painfully true if everyone played low status.) The skill of the art is knowing when one or the other serves a scene best.

I think Cuddy would say the same about life outside the experimental lab. It doesn’t make sense to try to out-rank an officer delivering a speeding ticket or to enter a job interview and sprawl across a desk or chair, looking to take up as much space as possible. Again, our societal standards of status give us good direction for what’s appropriate in any given moment. The most artful life players have the flexibility to choose which position and approach to apply in any given moment.

That said, who doesn’t want to be more confident, more present, more influential, or more authentic? The real power of Cuddy’s research comes in how we prepare for life’s big moments. We all face situations where we’re being evaluated: the social circle of the lunch table, a job interview, a first date, a public speaking engagement, a theatrical production, a tough conversation. Those who have historically struggled to find their power or raise their voices can turbo-charge their confidence and coherence with the simple, succinct, and elegant technology. Even those who play low-status characters or assume a socially acceptable lower status in a negotiation on purpose will want to enter that “scene” with their fullest faculties. If two minutes of taking a power position in private—in the car, in a stairwell, in the bathroom—helps lift confidence and lower stress levels, there’s simply no reason not to snatch the magic. It’s true for the Failure Bow like it’s true for the high-power stance. Given the choice, you do that voodoo.

Amy Cuddy’s TED Global 2012 talk in Edinburgh:

Pictures of example poses drawn from “Power Posing: Brief Nonverbal Displays Affect Neuroendocrine Levels and Risk Tolerance,” by Dana R. Carney, Amy J.C. Cuddy, and Andy J. Yap, Columbia and Harvard Universities, Association for Psychological Science, 2010.

[1] I wrote this post in a public library sitting next to a young guy—maybe 10 years old—playing a car-racing video game in silence. Twice in five minutes, almost as if on cue, he finished with a result he liked and raised his arms and chin in champion-like fashion. On the second win, he even beat his chest a few times before going all the way up. Gotta love it.

[2] Cuddy acknowledges in her TED Talk that in her classes, she’s seen a clear correlation with gender: students who assume high-power poses the most tend to be men and those who assume low-power poses the most tend to be women. That difference could trace to differences in testosterone levels, to societal approval for how we carry ourselves, or both. Neither takes away from the central conclusions of her research here: her main focus examines how our power in one stance compares to our own power in another.

[3] I love that we don’t have to have the emotional resilience to think our way into the reframe as well. We simply need to change our bodies to createthe shift automatically. I suppose the choice to do a Failure Bow is itself a conscious choice of reframing, but it’s a much easier choice than to simply “change how I’m feeling” by dint of will power.

These posts touch on the growth mindset we teach our Upward Bound students. It’s an idea that our students build on and that I believe really creates confidence and healthy risk taking. I just spent an hour talking about this with a student interviewing for college so it was exciting to hear the science and theatre of it too! Thanks Ted!

You’re more than welcome, Gisele. What a gift you’re giving your Upward Bound students by introducing them to the growth mindset idea. It’s that healthy risk-taking that I’m so eager to promote–that’s where the real creative leaps happen!