This past weekend, my partner Melissa and I attended The Death Show (A Recital), an intriguing community theater production in Hudson, New York. Simultaneously provocative, poignant, peace-giving, harrowing, and hilarious, the evening has left me thinking about the impact of death in my life—and how to bring its air-clearing quality into my classroom more purposefully.

The Death Show was conceived and crafted by Melania Levinsky and other members of the Walking the Dog Theater company. Each of the five players contributed mightily to the show’s success, reciting a seamless weave of poems, songs, and monologues. Some of the pieces had been tightly rehearsed (like the litany of diseases sung to the tune of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy); others rode improvisational waves in tune with our night’s specific audience (as when “Brother Death” walked silently through the cast and audience, tapping people on the shoulder to indicate that now was their time).

Most memorably, each cast member took the spotlight for a few moments to share individual reflections on the subject. All five of these stories proved deeply personal yet also universal, artfully articulating questions that rarely find the light of day. Each monologue was followed by an improvised “death” based on suggestions given by the audience before the house had opened— we saw “a clown dying of happiness during the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade” and “death by mascara while driving down the Taconic Parkway,” for example—and a ritual-like delivery of epitaphs for that particular player. As a whole, the show felt less like a play and more like an open-hearted conversation about the many roles of Death: tormentor, rib-tickler, priority-clarifier, ambassador to the other side, familiar companion.

After the performance, we went out with our dear friend Benedicta—one of the players—and a few other audience members for a drink. Not surprisingly, the show continued to cast its spell, leading us to share stories of our own experiences and perspectives on death. I realized that, for the most part, I’ve escaped any close contact with the Reaper’s blade. Yes, all of my grandparents have passed on but I wouldn’t say that I knew any of them particularly well. A classmate in high school died in a sledding accident, but I was just getting to know her. One of my colleagues at work took his own life this summer—and I have missed his presence—but our connection had always been more peripheral than central. A handful of my closest friends have gotten cancer or suffered heart attacks but all have survived the scare. I have never lost a parent, sibling, partner, or dearest pal. In most senses, that feels lucky. In the wake of last night’s performance, I wonder if my own living lacks a depth for lack of death.

Had I participated in the show as a cast member, I probably would have told the story of losing my beloved Ocicat, Madsen, five years ago. When I first picked her up ten years earlier, I had taken a ferry from the San Juan Islands of Washington state over to Victoria, British Columbia to get her—hop off the boat, get the cat, hop back on the boat—and we had been best buddies since. When I went away for a weekend and accidentally left a ground level window open, however, Maddie got out and never came back home.

For weeks, I struggled with whether to make every effort I could to find her or to face the likelihood that she was gone and I should let go. The thought of her waiting for me, cold and injured somewhere in the woods, haunted me for months, even as her odds of survival dwindled. I never found her collar or any other evidence of her demise. I only had the lasting hole in my heart to remember her by. It felt like a full year before I was able to imagine the joy of welcoming another feline beastie into my world. Death has broken my heart, but I know that (or I imagine that) the death of a pet and that of a human companion differ immensely.

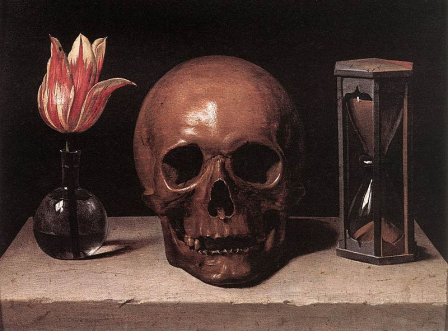

Our post-show conversation at the bar also stirred the memory of when I volunteered at a Palo Alto non-profit during graduate school and met a woman in her eighties named Amelia Rathbun. She had retired from her leadership of Beyond War, a group working to end the use of nuclear weapons, but still looked in on the surviving organization. When I visited her house for a meeting one evening, she brought me to her living room and lifted a silk scarf on a side table to reveal a bleached-bright human skull. “It’s important to welcome death into your home, Ted,” she advised me. “He’s one of the greatest teachers and friends you’ll ever meet.”

Amelia Rathbun was on to something when she welcomed death to her living room.

“Still Life With a Skull” by Philippe de Champaigne

Image from Wikimedia Commons

And there, Amelia reminded me, lies the precious paradox: opening the door to what we’re most afraid of actually can free us the shackles of our fear. When we remember that the end could be near, we can speak more honestly. We can choose more boldly. We need not pussyfoot—we can create and connect more authentically. Rather than welcome such wisdom, however, we in this culture tend to hide from death, trying to keep its icy hands as far from us as possible. We send our elderly off to community homes. We fend off the advance of age with botox and creams and fitness programs. When the physical end finally does come, we whisk bodies off and either cremate them or preserve them for a final viewing, rarely taking full stock of the final mystery: this body breathed with life and now lies still. Thinking we’re keeping ourselves safe from death, we shackle ourselves to certain shallowness.

I can now see that I need to find a way to welcome Death more directly into my classroom. If I’m trying to develop a learning space that promotes courage, creativity, and community, what better guest speaker could I invite? What better theme could I choose? Each group I teach does encounter Mystery Questions, an exercise where we anonymously write our most vexing questions about self, others, and life and the universe—and those often include inquiries directly about death and dying. When we read the questions aloud a week later, the ritual inevitably takes on a reverent and humbling tone. The kids are both moved and comforted to hear that others have struggles similar to—and different from—their own.

Inspired by the production’s spoken epitaphs, I’m also thinking about the idea of having students write their own obituaries—or maybe even having the group collaborate on writing each other’s. Clearly, this wouldn’t be an exercise for the first week of class—we’d need to know each other and have developed a requisite level of trust. With a semester’s worth of sharing, however, it could have memorable and long-lasting impact. When I took a leadership course in business school, we did a similar exercise, each lying with our eyes closed on a table, surrounded by friends as they read our obituaries aloud. I remember the peace of knowing I’d made a difference and the inspiration of having really been seen.

I most certainly intend to revisit the work of Joanna Macy, a Buddhist scholar, deep ecologist, and one of the most innovative teachers I’ve ever learned from. Joanna has done powerful thinking about what she calls Deep Time, helping us harvest the gifts of all our ancestors—from stardust and galaxies to parents and grandparents—and our descendants—those who will look back on the choices we made—alike. When we inhabit a larger time frame, death need not feel so final. We get to see its humor as well as its horror.

In her workshops, Joanna often uses a meditation from the Buddhist tradition that invites us to reflect on two facts: a) death is certain and b) the time and circumstance of death is uncertain. Allowing those realities to rise into full consciousness can feel painful but can also shake us awake to life’s miraculous quality, its resilient beauty, and the precious uniqueness of each object and being. The meditation, usually read slowly by a facilitator after group members have walked in quiet focus for a few minutes, works best when standing face-to-face with another:

Look at the person you encounter (stranger or friend). Let the realization arise in you that this person lives on an endangered planet. He or she may die in a nuclear war; or from the poisons spreading through our world. Observe that face, unique, vulnerable…Those eyes still can see; they are not empty sockets…the skin is still intact…Become aware of your desire that this person be spared such suffering and horror, feel the strength of that desire…keep breathing…Also let the possibility arise in your consciousness that this may be the person you happen to be with when you die…that face the last you see…that hand the last you touch…it might reach out to help you then, to comfort, to give water…Open to the feelings for this person that surface in you with the awareness of this possibility… Open to the levels of caring and connection it reveals in you.[1]

Even reading the words makes me more thankful for and more protective of the opportunity in each person I meet. I feel more compassionate.

Some might say such exercises dig too deep for teenagers. Experiences like these reach into spaces left undisturbed. And some would say the same for adults as well. Best to keep death as far at bay as we can. I respectfully disagree. As The Death Show artfully demonstrated, we can tell these stories. We can acknowledge these truths. And we can wake from this slumber. I’m eager to get started.

[1] From Joanna Macy’s website and from her book, Coming Back to Life: Practices to Reconnect Our Lives, Our World (New Society Publishers: British Columbia, 1998). www.joannamacy.net/engaged-buddhism/221-meditation-on-death.html

Good one, Ted. I like the face to face meditation near the end from Joanna. You know that Henry the Dog just died and did so very unexpectedly and while we were away for Thanksgiving. So, we return to an empty house and to no body. Rather, in about a week, we will receive his ashes. None of us were able to say goodbye. We were unable to hug either his dying body or his just departed body. We left a healthy, happy, barking dog behind and return home to a cup of ashes.

I am not home yet, but will be tonight. I know I will miss his big old body–a sometimes pillow for me, lying on the floor, my head feeling his chest move up and down. And, his ever-non-judging eyes. And his frequently wagging tail.

Jerry, I did not know that Henry had died while you were away. I imagine that ache of missing him will only be compounded by not getting to say a proper goodbye. The book and film Life of Pi speaks eloquently to that loss. If you read an earlier post I wrote this summer about losing our cat Piper and spreading her ashes, you’ll hear some more thoughts about honoring such transitions with intention. Maybe Piper’s example can provide at least some comfort or perspective. I’m thinking of you and the family. (http://tedwordsblog.com/2012/07/10/saying-goodbye-to-piper/)

Hi Ted, Thank you for coming to the Death Show, and thank you for your thoughtful write-up.

They are lucky students who have you. We the cast, in our pre-show preparations, often reflected on how many people we knew in the audience who were struggling with terminal diseases or who had recently lost loved ones. And reading that beautiful meditation at the end of your blog, I now wish we had had the presence of mind to somehow include in the show a real-time recognition of the shared impending worldly end for all of us in the room. Perhaps a meditation, or maybe just a chance to look at each other for a moment in that light. I will keep it in mind for the next one!.

Warmest Wishes,

Melania

Thank you for your thoughts here, Melania, and again, for the heart-opening show. I agree–it would have been powerful to look around the room and notice that these people, too, will someday die. One or more of them might even be with us when we die. There’s such a poignant real-ness to such meditations. Death isn’t just an abstraction.