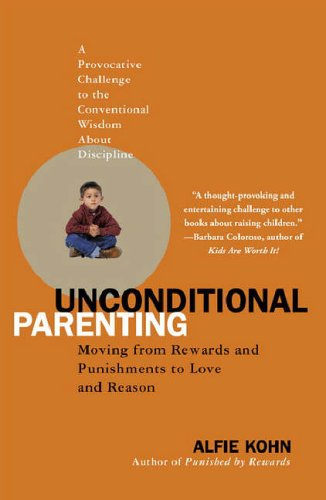

I’ve just started reading Alfie Kohn’s Unconditional Parenting: Moving from Rewards and Punishments to Love and Reason and I can already tell it will stir my pot. Kohn has no love for positive reinforcement. Quite the opposite, he considers it both dangerous and destructive. Given my investment in the topic and my eagerness to examine all sides of the approach, I know the book will make an important read. Good insights and new questions have already bubbled to the surface.

Alfie Kohn has challenged traditional techniques—and even many alternative ones—in the field of education for years. Two of his earlier books, No Contest: The Case Against Competition and Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A’s, Praise, and Other Bribes, first articulated his contrarian stance and earned him predictably polarizing reviews. Some see his work as revolutionary. Others think he’s off the deep end.[1] I get the sense that those in the latter camp have heavy investment in the models he critiques. That inkling of mine doesn’t automatically make him right, but it does lead me to question my own knee-jerk resistance to his take-down of positive reinforcement.

In the first few chapters, he’s already raised valuable points. Most often, Kohn argues, positive reinforcement works to control behavior not in the direction of a child’s growth or natural unfolding but instead in the interest of compliance, convenience, or adult preference.[2] We use our techniques to develop docility or reward well-behavedness rather than to cultivate curiosity, caring, or creativity. Maybe this critique should be aimed more at curriculum and assessment design—What skills and behaviors do we strive to develop? How do we best measure those? Should we focus on attitudes and mindsets instead?—but it’s still a valid concern for positive reinforcement as well.

Kohn also notes how, by design, positive reinforcement focuses almost exclusively on behavior, leaving out information about a learner’s emotion or intention. Maybe I can elicit a particular action I’m looking for, but if the learner chooses that action to please me or to get a reward rather than choosing it for the joy of its own doing, have I really succeeded? What if she can demonstrate the behavior but does so with hostility or emotional numbness? Maybe my learner struggled because of troubles elsewhere in her life and so was acting out in unpleasant ways. Now she’s learned that she’ll get my approval—earn her reward—only when she puts those feelings away. She may have succeeded with the specific task, but she has also added significant content to what Robert Bly calls “the long bag we drag behind us,” those emotions and ways of being we excise from self-expression to avoid the shame they bring.

Kohn’s main argument is that parents should offer children unconditional love, celebrating that they are rather than what they do. Positive reinforcement, he asserts, automatically teaches a child that love comes with conditions. Succeed at the task I’ve put in front of you and you get my delight and approval. Do the behavior I want, we celebrate. Sure, kids will take praise over punishment or over nothing at all. What they really want and need, though, is to be seen and loved without having to earn that approval.

Again, these are all fair challenges that deserve—and will receive—further consideration during my sabbatical. For sure, I don’t want to buy in to or promote a technique that actually does more harm than good. I expect I’ll include much of those musings in this space as I go. I will be curious to hear Kohn flesh out his arguments further and I’ll be especially keen to hear his suggestions for alternative approaches. In the meantime, I’ve got questions of my own for him.

Kohn says, for example, that extrinsic rewards necessarily diminish intrinsic motivation. If we work for a reward, that undermines the joy we receive from the action itself. In some cases, though, I’ve experienced the opposite. My partner Melissa and I have different standards for cleanliness in our home. I wouldn’t call myself a slob, but neither would I qualify as a neatnik. She has patiently and consistently rewarded me for efforts I make to help meet a higher standard. She never carps or chirps acerbically. She offers a simple “thank you” or a hug and leaves it at that. Even though I know exactly what she’s doing, it’s had an effect over time. I would never have found an intrinsic motivation to clean more often or more thoroughly. That desire simply wasn’t in me. But I have now developed a positive association with doing so. I dare say I’m even coming to enjoy it on my own. When I spent these past two months in California on my own, I kept my space much cleaner than I ever had before even though I was living by myself. Rather than weakening intrinsic motivation, the reinforcement has created it.

Yoga demands balance…AND creates it, whatever the original motivation.

—–

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Sometimes, too, the motivation behind the behavior actually doesn’t matter. What does matter is doing the behavior. As Stanford psychologist Amy Cuddy describes, simply taking certain physical positions can create a chemical cascade in our brains that creates a new mood, a new confidence, a more focused creativity. Suddenly, clouds lift and joy moves in. The same can hold true in the practice of yoga. Maybe a novice comes to yoga class because he wants to get toned and trim. He has no spiritual aim in mind; he’s seeking no Self-revelation. He only wants to look good so he’ll have a shot with the hotties in spandex.[3] Even without any noble intention, though, the practice will change his insides. Standing and sitting in dynamic, balanced poses; aligning breath with movement; settling and calming his mind: every class will lead him closer to his spiritual center. Finding his Self more fully might eventually lead him back to class for deeper reasons.

I’ve seen positive reinforcement help build intrinsic motivation on the softball field and in the classroom as well. Maybe the success comes at cross-currents to the method’s downsides, but it still comes. When I encourage my softball girls to stay focused in their hitting drills—even if they’re resistant or they wouldn’t choose that work on that day—they start to develop their skill. Once they have the skill in place and achieve success during a game, they start to want more. They attack the tee or tossed balls with greater focus and ferocity without my having to do a thing. The reps through resistance built their ability. The increased sense of agency fueled their intrinsic motivation. In class, students learn how to annotate their books, write more coherent essays, or ask better questions of their peers. The more they find the joy of mastery, the more they come to class eager to learn.

I don’t pretend to know all there is to know about positive reinforcement. Far from it. As a result, I will take Alfie Kohn’s critique, however blistering, into honest consideration. At the same time, I won’t reflexively shrink in submission to the challenge. I’ve got questions for his questions. I know—I can feel—there’s some truth here, and it’s good truth. I’m confident I’ll keep finding it.

[1] For the record, he was a great inspiration when I was in college and grad school.

[2] Kohn usually talks about carrot-and-stick motivations so he’d include punishment and reward alike. He also makes special mention of his concerns about positive reinforcement specifically, partly to address folks like myself who eschew punishment but still look to shape through affirmation and acknowledgment.

[3] When we study Hinduism in World Religions, I joke with my students that this branch of yoga stems from the Assaghidardha tradition. As in, you do this yoga, your ass’ll get harder.

Hi Ted –

I enjoyed reading your reflection. This is the first of your posts that I’ve read and the topic caught my eye, especially as a new parent myself.

I should probably say first that the only thing I know about Kohn’s work is his articles against homework, some of which I tend to agree, though definitely not wholesale.

In terms of positive reinforcement, I wonder if he has considered the research that shows that behaviors can change our mood and beliefs. It’s the old, “fake it till you make it.” Acting like you are in a good mood can get you into a good mood. In religion, repetitive actions, like praying, are not something you do just because you believe, but they reinforce the belief. Additionally, research on addictions show that knowing intellectually what you should do doesn’t actually effect a change in behavior. For example, people who are overeaters can mentally understand how much they should eat, but still cannot stop themselves from overeating. The most effective treatments can be ones that change the behavior first.

It seems counterintuitive because as intelligent beings we’d like to believe that we behave rationally and have full control over our actions, but I don’t believe it’s as conscious as that.

Anyway, something to add to your reflections!

Julie

Hey there, Julie.

Thanks so much for reading and for your reflections. I so agree with you: we barely have any clue just how non-rationally we act. Or how much strength we have inside us! Check out my earlier two-part post on “The Transformative Failure Bow” for more conversation on the “Fake it til you make it” phenomenon. (If you click on the Archives link at the top of the page, you’ll see the posts there.)

I’m so glad you got to the blog. Thanks again for stopping by.

Hello Ted,

I was very interested in your reflections on Alfie Kohn and reinforcement and praise, as I am a Montessori teacher (who was steeped in Alfie Kohn’s approach to engendering intrinsic motivation rather than creating extrinsic dependence in students) and am now studying ABA, and am having some cognitive dissonance. I encounter children who need ABA in order to function optimally in the environment, but this is such a tricky business, and I am interested in any further musings you may have on the meeting of these two areas of thought.

Hello, Bonnie.

These are huge questions you’re stepping into and I don’t think they have easy answers–but (or, AND) the exploration will almost certainly prove fruitful.

I’d recommend Carol Dweck’s growth mindset work as a start. Praising intelligence or native ability is actually debilitating. Praising (i.e., reinforcing) effort, struggle, and resilience (i.e., process) proves supportive. You can see my Mindset 101 post (http://tedwordsblog.com/2012/10/17/mindset-101) and then read Dweck’s Mindset book as a start.

I’d be happy to talk more, too.

Thanks for your reflections,

Ted