Mindfulness has emerged from obscurity and has begun blooming in far-reaching fields. Whether in business or education, health care or athletics, law and criminal justice or any number of spiritual communities, increasing numbers of voices promote the practice. Better results through deeper presence, you hear. Success through non-striving. A practical panacea. These are heady times for those of us working in the mindfulness arena. Anything seems possible.

Mindfulness has emerged from obscurity and has begun blooming in far-reaching fields. Whether in business or education, health care or athletics, law and criminal justice or any number of spiritual communities, increasing numbers of voices promote the practice. Better results through deeper presence, you hear. Success through non-striving. A practical panacea. These are heady times for those of us working in the mindfulness arena. Anything seems possible.

Of course, any healthy skeptic could label this tangible surge a passing fad, fifteen minutes of fame for a self-help delivery du jour. From that perspective, the seeming golden age might actually represent a bubble waiting to burst. I don’t subscribe to that notion, but it does provide a worthy challenge. As a willing investor in youth programs recently asked me, how do we ensure long-haul, systemic change with all this interest in mindfulness?

Here are seven suggestions to start.

Keep at it at a natural pace.

We can whip ourselves into a frenzy about the need for mindful programs without much effort. We sense the pain of poverty, violence, substance abuse, alienation, and deep-rooted oppression. We see that suffering, our hearts break, and we call to action. On the flip side, we just know the positive possibility of this work. Greater resilience! Improved decision-making! Deeper calm! Oh my gosh, how do I get this to as many people as possible?

While understandable, neither strident urgency nor unbridled enthusiasm further the cause in a sustainable way. Both pull us off-center. Both lack the kind of durable patience that emerges more naturally from present attention to the moment. Breathe. And breath again. Now…what needs to happen next?

Preserve the integrity of practice.

As one of our first steps, we need to ensure that practice matches our preaching. Even if we believed in the value of water sports, we wouldn’t throw a beginner into the ocean without first offering guidance from an experienced swimmer. Similarly, we shouldn’t assume that an article (or a blog post) on mindfulness gives us the license—literal or figurative—we need to jump into teaching mindfulness to others. Without needing to veer into preciousness or elitism, there is real value in holding to a standard. Patience, perspective and sensitivity come most when we embody these principles we espouse. That takes time and steady effort. And should precede or supersede any rush to action.

If you’re looking to learn to swim in the waters of mindfulness, look for an experienced teacher. Or, find a seal of approval.

Image courtesy of geograph.uk.

Invest in mindfulness teacher trainers.

Because of that need for congruent practice, the biggest bottleneck in ramping up effective, wide-reaching mindfulness programs remains the lack of well-trained teachers. And we have even fewer folks qualified to train them. Any philanthropist looking to further the cause would do well to fund a high-quality teacher trainer, freeing that person from the stresses and demands of other work to focus on the more crucial tasks at hand. This one lever promises to flip a whole bunch of levers below it, an exponential amplifier of that original investment.

Support key research.

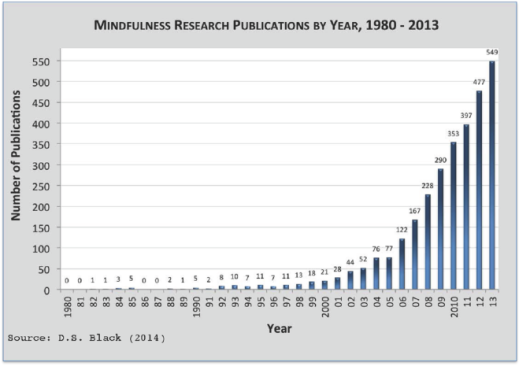

Mindfulness research has exploded in recent years, partly because initial reports have appeared so promising.

Mindfulness research keeps growing, a reflection of societal interest in its benefits.

Much of that investigation has lacked a certain rigor, however, and much of it has raised further questions.

• Which components of mindfulness training really make the active difference? Is it mindfulness skills, group experience, or quality of care from the teacher—or some combination of the three?

• Knowing we want to pass on an integrity with practice, what minimum “dosage” of exposure to mindfulness gets us that ongoing, long-lasting integrity?

• How much training does a mindfulness teacher need before developing requisite skill and sensitivity?

Each of these inquiries challenges assumptions we might make and can preempt erroneous claims or misguided initiatives.

Determine a common “scaffolding” for teaching mindfulness.

As societal interest in mindfulness has swelled, so has the supply of related curricula. Not surprisingly, some prove effective and some, not so much. The strongest and most widely recognized—like that of Mindful Schools in Oakland, CA or the Mindfulness in Schools Project of the UK –follow common threads. Establish connection and context, build attention, and invite curiosity and kindness before moving onto more complex skills like suspending reactions or watching thoughts and feelings. Such a backbone to mindfulness training helps with several of the suggestions above. We find an appropriate pace. We help preserve quality and integrity. And we make effective research a heck of a lot easier.

What’s the best scaffolding to ensure quality mindfulness teaching?

Photo courtesy of Nicholas Jones and Creative Commons.

Encourage interdisciplinary collaboration.

David Germano and his colleagues at the University of Virginia Contemplative Sciences Center have initiated thorough organizational change by targeting key players across traditional bounds within the university. By integrating all 11 schools—from professional programs in business and medicine to undergraduate liberal arts and sciences schools—the center gains layers of perspective that generate original insight. That broader insight, in turn, ensures wider buy-in across the entire school.

Reach out into the community.

At the Mindful Miami conference a few weeks ago, organizers had pulled together an impressive array of presenters from local government, health care, criminal justice, education, professional sports, social services, and research agencies. You could almost feel the resurgence among folks who had previously felt isolated in their efforts. Each of those folks now knows they’re part of a larger effort and they can trust that, together, they’re going to impact the wider Miami community. The rising tide means we are not alone. We need to find our allies and join with them.

This current interest in mindfulness offers a precious and seemingly-fleeting opportunity. In the words of the Roman Germans, carpe zeitgeist. At the same time, as Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder of the acclaimed UMass Center for Mindfulness, reminds us, the practice has a long history. In that light, we do well to place our efforts in the service of a long-term future. Bringing mindfulness to wider circles won’t work as a quick-fix solution. It will take time. It will take effort. As always, it will take practice.

Ted DesMaisons is the founder and principal of Anima Learning, a collaborative consultancy that honors and feeds the spark of curiosity in leaders, educators, and individuals. He also serves as the US Coordinator for the UK-based Mindfulness in Schools Project.