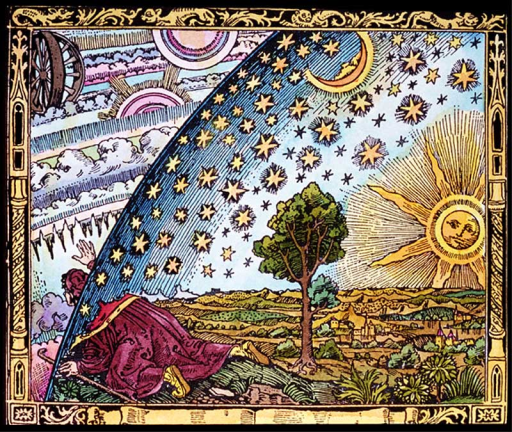

The caption on Flammarion’s The Universe and Man:

“A missionary of the Middle Ages tells that he had found the point where the sky and the Earth touch.”

Part 1 of this three-part post introduced a working definition for spirituality—the whole-person practice of awakening, feeling, and expressing a connection to larger Mystery and deeper meaning—and for improvisation—the in-the-moment art of active creating in relationship to the many offers coming from one’s inner life and immediately surrounding circumstances.

Part 2 examined the ways that improvisation connects us to divine play, mindfulness, interdependence, Shadow, and paradox—each components of what many consider the spiritual life.

Part 3 here goes even further to explore the ways in which improvisation might represent a participation with larger forces around, behind, beyond, or within us.

In “The Universe and Man,” an ancient wood engraving that serves as the motif for this blog, a shepherd reaches through the visible curtain of his known world to catch a glimpse of the beauty and order that always lies behind it.[1] I have always imagined the shepherd as a humble seeker, perhaps surprised to have received such a clear vision, but also curious, willing to step into this new way of seeing. His body connects to the ground, as if thunderstruck or waking from sleep, at the same time the right arm lifts up, raised as if in praise or wonder. Maybe the vision came in response to a prayer or a daydream. Maybe he has concluded a quest. Whatever the path, the shepherd has called and the Universe has responded. He has found the point where the sky and the Earth touch. His life can never stay the same.

So it is with improvisation, if we turn our attention in the proper direction. We step on stage or onto a dance floor or into a concert hall and we play. We ask for a choreography to come and it arrives. Sometimes we need the ritual of our warm-ups to charge the space but our sincere call behind the curtain of what’s visible almost always connects us to a larger force that’s not. We tap in, and something moves through us. We can be blown away by what we find, but in those special moments, we see anew. We find ourselves changed.

Tending the Third Thing

My San Francisco colleague Lisa Rowland likes to say that two improvisors create a third thing on stage, something outside and separate from—and yet connected to—the two of them. Their job as actors is to serve that new creation rather than to serve their own hopes or wants. Ego concerns matter little when other more pressing questions demand attention: What does this story need? What’s being told through us? The performers have called. The third thing has arrived. Now they all dance together.

Oddly enough, the word “spontaneous” derives from the Latin sponte, meaning “of one’s own accord, willingly, of one’s free will.”[2] In improvisation, we willingly choose to engage with these hidden creative realms. Again, we may not always stop to notice that we’re doing so, but we are doing so. No matter our experience or processor speed—and trust me, folks like Lisa and her compatriot BATS performers in San Francisco or TJ and Dave in Chicago have plenty of both—scenes and songs still unfold too quickly for conscious explication. We’re still relying on ideas that come from…somewhere else. In yet another improv paradox, we employ our free will to let ourselves be used.

Does this mean improvisors are possessed when performing? Are we asking to dance with demons and hoping the friendly ones arrive? I don’t think so. It’s more that we’re participating than being possessed. We’re asking for aid from beyond what’s visible and tending to that support when it shows up. Such help might indeed come from God or Ganesh or some other previously-named deity. It might stem from Life, or Light, or Love. The name of that source doesn’t matter so much. Choosing it and connecting with it does. We’re a conscious instrument playing an unconscious—or perhaps a more-than-conscious—song.[3]

New Improv Exercise #1: “Line-at-a-Time Deities”

During our recent Improvisation and Spirituality workshop, Cort Worthington and I introduced two new tools to make this connection more explicit.

The first leaned on a standard shared control exercise, Line-at-a-Time drawings. Cort coached our paired participants through the instructions, suggesting that they start by marking their blank sheet with two dots about two thirds of the way up the page and then leave an empty space at the bottom for future use. Then, in silence, they should alternate making one line, mark or gesture on the page until a complete image of a hitherto unknown deity emerged. Once the drawing felt finished, the pair could name the deity by spelling out its name one letter at a time in the blank space at the bottom of the page. The final direction was to go back and forth, sharing impressions of the deity that had just been created. For what might people pray to this god or goddess? How might you describe the deity’s tone or attitude? What was his or her ‘personality’ like? Each addition should build on earlier descriptions in fine “yes-and” fashion, the deity’s quality emerging as a shared improvisation.

I don’t know why I was so surprised, but I was stunned by the power and vitality of what emerged. We met Meditanzia, a calming and light-hearted goddess who helped maintain daily spiritual practice and Hural-Mago, a randy god who visited to encourage the peace that follows sexual release. We got to know the cheerleading support of Laren and the gracefully feminine acceptance of “Me.” Each deity we had called forward came through strong and clear, with good wisdom to offer. Each had been that “third thing,” well-tended.[4]

New Improv Exercise #2: “Invocation”

A second improvisation and spirituality exercise that Cort and I introduced derived from “Invocation,” an experience I first learned in a session with Rebecca Stockley and Matt Smith at the Applied Improvisation Network world conference in San Francisco, fall of 2012.[5]

In this ‘game,’ Rebecca and Matt asked four performers come to the front of the room and got a suggestion for an everyday, mundane object: hat, lamp, refrigerator, knife, or so on. Together, the players took a moment to bring to mind a specific example of that object from their own individual histories. Then, when moved, each spoke in snippets about their object in third person form. With the suggestion of ‘lamp,’ the first performer might have said It offered a soft light, with its gentle bulb behind a handwoven lampshade, beads dangling off the edges. The second could have relayed Even when lit, it reflected a dull shine, gun metal grey like the rest of Dad’s apartment. Again, each player spoke of a specific object from his or her own experience. All players spoke about the same type of object.

After a time of such 3rd-person observation, the players shifted to a 2nd-person perspective, speaking to the object as a “you.” You gave Grandmother enough light to knit by and that kept her sane during the long nights after Grandpa was gone. Or You matched Dad’s flannel suits, gray and boring, somehow lifeless even through the shine. Once each had contributed a round or two from that point of view, the players again switched to a round of “Thou,” a bit more formal and perhaps reverent in relationship to the object. Thou hadst traveled many miles and heard many stories, carrying a nobility in thine humility. Or Thou kept secrets, I’m sure, a steely knight of the bedside. With each utterance, the four objects gained in complexity and depth.

For the last round, the performers spoke as if they themselves were the objects, taking on its 1st-person perspective: I always appreciated sharing silence with you. Those nights were sweet even without words. Or I never wanted the burden I carried. My job was to shed light on the truth, not seal it away. These revelations from the objects themselves proved surprisingly poignant and powerful. Simply by switching viewpoints, the performer’s had worked the mundane into the profound. They had asked for the wisdom of that object—we could call it the Platonic form—and wisdom had arrived.

That day, after a couple rounds in that manner, we wondered aloud what it might be like to try the exercise with more provocative ‘objects.’ What if, instead of choosing a lamp or a hat, we instead chose “Mother,” “Ambition,” or “Money?” What if we invoked an emotion like “Joy” or “Shame?” We played a bit with the notion in small groups but ran out of time before having the chance to try on a larger-scale performance.

The suggestion stuck with me all year until our workshop this past July. Cort and I first trained our participants in the Invocation exercise as I’d learned it from Matt and Rebecca. After that, we seized the opportunity to dive into a cycle of more experimental iterations, going with “Fear,” “Hope,” and “Lust.” Each round proved powerful, especially as those in front learned to speak from their own personal experience rather than from an abstract understanding of the term. Whenever we finished, it felt as if that emotion had entered the room as a teacher, offering unexpected insights and valuable challenges.

I wonder now what it would be like to try “God,” “Mystery,” “Mind,” “Boredom,” or any number of other ‘objects.’ What about “Music” or “Laughter” or “Inspiration?” Or elements like “Fire,” “Air,” and “Water?” The possibilities seem endless. Trusting the technique of collective improvisation, each person speaking truth from their own experience, we could ask for and participate in whatever wisdom we need.[6]

Spiritual Practice, Improv, and Pronoia

As we do in such exercises, we connect with spiritual powers to invoke new worlds in our everyday lives. Every moment, we call something into being. Our attention shifts, our intention chooses a focus. New thoughts create new perspectives and, in turn, generate new experiences. If we focus on the spirit of worry, we bring that god into being. If we concentrate on joy, we engender joy. We ask as we inhale. We create as we exhale. Again, even when we’re not conscious of such creation, we’re still doing it.[7]

Contemplative improvisation gives us the chance to get more skillful with our invocations, to become more conscious of what we call into our world. We can learn to delight in serving the third thing. We can practice creating with the people and circumstances we encounter instead of fighting them for control. Like the shepherd in The Universe and Man, we can tap the order behind the ordinary, simultaneously grounded to earth and receptive to revelation.

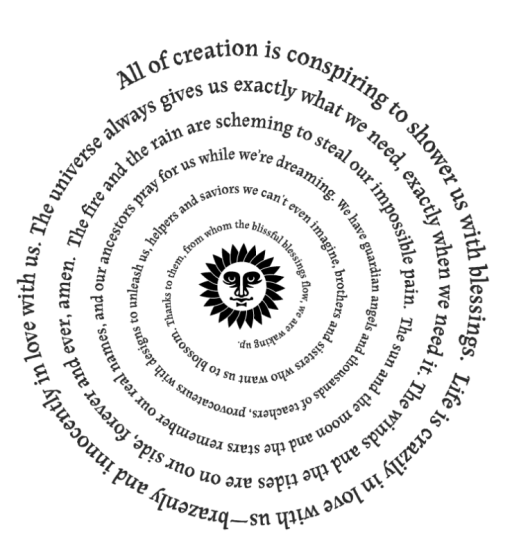

In this way, improv becomes a spiritual practice of pronoia, the belief that the world is conspiring to support you and shower you with blessings.[8] We make a call with our intention—and then simply pay attention for the opportunities and wonders that seek us out. We shift our weight into the dark of the unknown, trusting that the road will rise to meet our lifted foot. Allies emerge and the next line of our lives becomes clear. Characters reveal their truer traits. At the end of our days, without directing, we have participated in the wonder of an unfolding Reality. We have played. And, like the gods, we have created.

[1] Some version of this piece may date from the 16th century but it is best known as published—and perhaps created—by French astronomer Camille Flammarion during the late 1800’s in L’Atmosphère: Météorologie Populaire. According to Wikipedia, Flammarion was quite the spiritual seeker himself.

[2] From the Online Etymology Dictionary entry for “Spontaneity.” http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=spontaneous&allowed_in_frame=0

[3] When I have conducted weddings, I have always invoked the spirits of the place and whatever ancestors and loved ones could not attend in person. I imagine those prayers as a shout-out to the universe: Hey four-leggeds, hey two-leggeds, hey earth and sky beings, take notice. Anyone who wants to support the joining of these two, come on down. We’re forming a circle and would love your help. We’re not asking them to take over. We want to celebrate with them.

[4] Tips for leading Word-at-a-Time Deities include:

a) Remind folks to maintain silence throughout. The quiet helps keep the receptive mood.

b) Encourage an openness to the nature of shared creation. If they find themselves wanting to control the drawing by making-one-gesture-but-leaving-the-marker-on-the-page-for-a-long-time, suggest they acknowledge that feeling and let it go.

c) Have at least two colors available for each drawing but ask each artist to put their marker down after each gesture. That way, their partner can use the same color if they’re drawn to—so to speak—and the process slows down a touch.

[5] Funny story: I attended Rebecca’s and Matt’s session largely because I had heard great things about their teaching. When Rebecca asked for volunteers who “know what an Invocation is,” I proudly stepped forward, eager to impress with my Divinity School training. Why, yes, invocation means ‘to call into being’, stemming from the root ‘voc’ as in voice or vocalize.

As other volunteers made their way to the front of the room, she reiterated “I need to make sure those of you coming up know what an Invocation is.” One person reconsidered and returned to their seat while I remained up front, smugly beaming and waiting for my chance to shine. Invocation. Yeah, I got this.

It was only when Rebecca started explaining a novel improv game that I realized I had absolutely no clue what she was talking about. I only knew that it was no kind of invocation I’d ever done before. I sheepishly dropped my shoulders and slunk back to my seat, interrupting Rebecca with a mumbled explanation that trailed off into nothing: Oh, I’m sorry. I think I was thinking of a different term that doesn’t really have to do… Rebecca sighed—and I imagined shook her head in disbelief—and got another volunteer to come up. So much for my glorious first impression. J

I later found Matt at a lunch table and recounted the tale. To my relief, the story provoked much shared laughter and initiated a cherished friendship. The same held true when I finally got to tell Rebecca.

[6] Out of our brief experience with this modified version of Invocation, I offer a few tips for players and trainers:

a) Keep each utterance short. Think of your offerings more as mosaic tiles than monologues. What you say will form a picture with your partners’ words.

b) Maintain a brisker pace. While each line deserves a beat or two for settling, step forward with confidence and trust that words will arrive as needed.

c) Speak from your own perspective. If doing the standard version, choose an object from your own memory. If doing the newer version, share from your experience with or perspective on that ‘object.’ How has that emotion or character played out in your life?

d) Offer the chance to opt out. If you’re taking on the exercise authentically, it’s bound to expose some vulnerability. That’s part of its power. That said, it may dive into depths that remain too tender for exposure. Give your players a mechanism to pass, whether that means keeping an alternate sharp in the wings or taking another suggestion altogether.

[7] Maybe this is how and why addiction can seem like possession. We’re so unconscious of the ways we take part in creating our compulsion that it seems some outside force has taken us over.

As an improvise and witch I love these offerings. I will pass these on to my friends and fellow priestesses. Thank you!

Thanks for reading, Georgie. I’d love to hear more about how you see these thoughts connecting to your experiences as a priestess!

this is a gift. connecting improvisational play with the spiritual experience is something that can take us to the heart of both. i’ve made a similar effort, though more for fun, perhaps. http://www.deepfun.com/fun/2012/12/games-for-the-spirit/

Thanks for the link, Bernie. Great stuff!

Ted, as I think I mentioned elsewhere, but I’ll say again that you are writing my heart and passion and very soul’s path on these topics -I’ve been calling it Lila ( Sanskrit for “Divine Play”) and doing Lila Retreats 🙂 I love the research and thought you’ve put into this, thank you. And if you didn’t know Pronoia is my favorite word (is even tattoed on my body, underneath my divine donut.)

I so wish I was at your last retreat and hope that we can play together in the near future. I made the happy discovery this morning (as I mentioned to you on facebook) that Osho expounds on the 110th tantric technique “Gracious one, play. The universe is an empty shell wherein your mind frolics infintely.” -You will LOVE this…check it out here: http://www.meditationiseasy.com/mCorner/techniques/Vigyan_bhairav_tantra/110.php

Fantastic, Leif. Thanks for the link–I’ll look forward to checking it out–and we’ll keep you posted on the next workshop. Cort and I (and Lisa and I) are intending to offer a second round of each next summer, if not sooner.