[This is the second half of a two-part post. Part 1 can be found here.]

Negative Reinforcement (R-) makes a wanted behavior more likely by taking away or reducing something the learner does not enjoy. It “eliminates an aversive,” as they say in the field. In this sense, it’s a kind of relief from unpleasantness. Negative reinforcement would work well on me if I were in a super-loud bar, for example. You could get me to do a whole bunch of things I might struggle to do otherwise if you supported my behavior by turning the noise down, down, down. Another example: a horseman trying to get his animal to turn will apply pressure with the reins. When the horse turns toward the reins and the pressure stops, that’s negative reinforcement at work.[1]

Negative Reinforcement (R-) makes a wanted behavior more likely by taking away or reducing something the learner does not enjoy. It “eliminates an aversive,” as they say in the field. In this sense, it’s a kind of relief from unpleasantness. Negative reinforcement would work well on me if I were in a super-loud bar, for example. You could get me to do a whole bunch of things I might struggle to do otherwise if you supported my behavior by turning the noise down, down, down. Another example: a horseman trying to get his animal to turn will apply pressure with the reins. When the horse turns toward the reins and the pressure stops, that’s negative reinforcement at work.[1]

When a horse turns in a desired direction and the pressure on the reins loosens, that’s negative reinforcement. Of course, some horses keep going in circles no matter the feedback.

…..

Image courtesy of freedigitalphotos.com

The mistake-prone softballer will experience negative reinforcement when she makes the play correctly and hears her coach stop nagging.[2] The kid who tends to stay out late might find chores reduced when he comes home on time. At the messy one’s first gesture towards cleaning the kitchen, the cleaner partner might quietly do the kindness of relieving some other burden: taking the dog out for a walk or offering a ride to work the next morning. In each case, the movement toward the desired behavior elicits a reduction or elimination of something unpleasant.

Positive Reinforcement (R+) accelerates or increases a behavior by adding something desirable. Raises, honor rolls, bonuses, and the like usually strive to serve as positive reinforcement. Though they may unwittingly undermine their own cause, many parents and teachers intend praise the same way. In TAGteaching, the “click” that says Yes, that’s it! becomes a reinforcer. As with the three other forms of operant conditioning, the positive reinforcement most tailored to the specific learner will be most effective. Chocolate and candy will work wonders for some folks. They won’t do a thing for me—I don’t eat sugar.

Positive Reinforcement (R+) accelerates or increases a behavior by adding something desirable. Raises, honor rolls, bonuses, and the like usually strive to serve as positive reinforcement. Though they may unwittingly undermine their own cause, many parents and teachers intend praise the same way. In TAGteaching, the “click” that says Yes, that’s it! becomes a reinforcer. As with the three other forms of operant conditioning, the positive reinforcement most tailored to the specific learner will be most effective. Chocolate and candy will work wonders for some folks. They won’t do a thing for me—I don’t eat sugar.

In the case of our softball example, a coach might note a properly-made play as the team returns to the bench after a defensive inning. Probably the more powerful reinforcer will be to increase the athlete’s playing time. When the wayward teen comes home on time, maybe he finds a gift certificate on his pillow for his favorite pizza place. Or maybe he gets a sincere smile and warm welcome from his folks. The moment the messier partner does clean up—or even begins to do so—would be a good time to play a favorite song or walk through the kitchen wearing a preferred perfume or cologne. In many homes, a simple Thank you is enough.

A Positive Reinforcement Spectrum

The principles of operant conditioning suggest that behavior can be shaped using any of the four quadrants. That said, those of us in the positive reinforcement community—TAGteachers, clicker trainers, members of the Positive Coaching Alliance, and the like—train from the premise that positive reinforcement works best. It’s not a cure-all and it takes hard work: an effective teacher must get crystal sharp about which behaviors she wants to shape and which steps will best help her learner get there. When executed skillfully, however, positive reinforcement draws out the fastest, deepest, most durable and most joyful kinds of learning. Humans and non-humans alike: they keep coming back for more. The progress becomes a reinforcer all its own.

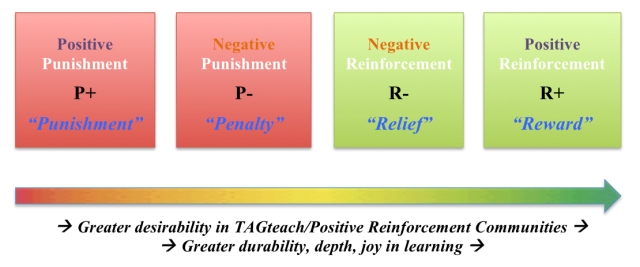

If we take the four quadrants from the operant conditioning 2 x 2 matrix and lay them out from least desirable to most desirable, we generate the following spectrum:

As I make choices about working to shape behavior in my classroom and at home—or about shaping my own progress—I try to keep this spectrum in mind. When I instinctively generate an internal response that seems or feels to me like punishment, I challenge myself by asking How can I at least move my reactions toward positive reinforcement? Maybe I’ll only slide one box over in the heat of a moment, but it makes a difference. In other moments, I realize I can do my best to stay neutral and buy time to make a wiser choice. Over time, my instincts have followed my intention. More and more often, my mind generates ways to reinforce the behavior I want rather than railing against what I don’t. I find my students have become more joyful as a result. I know I have.

The Buddhist Twist

The Buddha has something to say too.

…..

Image courtesy of http://sathyasaibaba.files.wordpress.com/2010/06/buddha-wallpapers-photos-pictures-h2o-lily.jpg

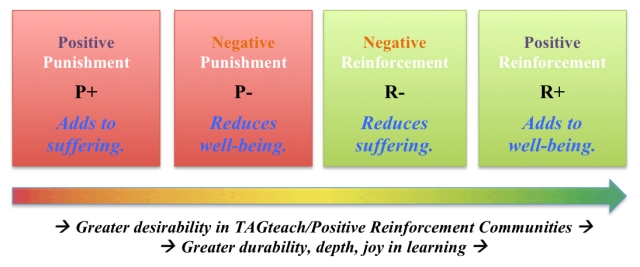

Among his many sage lessons, the Buddha taught that “Right Intention” consisted of two elements, seeking the abiding peace of enlightenment and ending suffering for all beings. In other words, build well-being and reduce affliction. For those still struggling to grasp the four quadrants of operant conditioning, we can overlay the Buddha’s words and gain even more clarity. Does the box deal with well-being or suffering? Are we talking about adding or reducing?

Teasing out the answers generates a new Buddha-influenced operant conditioning 2 x 2 matrix that looks like this:

When we pull these four boxes into a second spectrum, one can see that the Buddha would agree that we do best to lean toward the right pole. Reinforcement achieves the twin goals of Right Intention. Punishment goes against them.

I don’t mean to sound flippant or reductive about one of the world’s great religious traditions. The Buddha didn’t clicker train his disciples. Still, I find the language of suffering and well-being helps me ‘get’ the four options of operant conditioning in a much clearer way. I’ll bring more Buddhist principles into the blog when I write my next posts about a similar—but also surprisingly different—feedback matrix and spectrum. More to come…

[1] Note the application of a mild aversive here. In that moment, one could argue that the horse receives some ‘positive punishment’—the pull on the reins—for continuing to trot straight forward. The negative reinforcement comes when the pressure lets up. What’s key is that the let-up happens when the horse makes a choice. That will be a predictable consequence for the behavior of turning into the pull. In contrast, the ‘punishment’ of the pressure to turn doesn’t get applied in any consistent or recognizable pattern.

[2] It kills me how many coaches will continue their nagging even after the athlete has succeeded. As if the original, unhelpful hector weren’t bad enough, now we add in something like “Finally! Now why couldn’t you have done that before?!?” Let it go, Coach. Let it go.

[…] ← 4 Reasons We Avoid Our Inner Knowing–and 7 Things We Can Do About It A Positive-Minded Primer on Punishment and Reinforcement–with a Buddhist Twist (Part 2 of … […]